Analysis Of Competing Hypotheses Software For Mac

- Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) is a free computer program used to evaluate multiple hypotheses. ACH software can be downloaded for free at Pherson.org. You will also find instructions and tutorials for the ACH software at the Pherson Associates, LLC web site. This is an excellent tool designed by professional analysts.

- An analytic technique created at the CIA, ACH helps you analyze complex situations with multiple hypotheses and countless pieces of evidence. Multiple people can collaborate on a single problem, and ACH will compare everyone's analyses and pinpoint the precise areas of disagreement, allowing for a more focused debate. Burton/Analysis-of-Competing-Hypotheses.

| Died | 21 August 2018[1][2] |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Intelligence analyst |

| Nationality | American |

The analysis of competing hypotheses (ACH) is said to an unbiased methodology for evaluating multiple competing hypotheses for observed data. It was developed by Richards (Dick) J. Heuer, Jr., a 45-year veteran of the Central Intelligence Agency, in the 1970s for use by the Agency.

Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) For more info, read Heuer’s Psychology of Intelligence Analysis Why? To improve intelligence analysis by focusing on the mindset that guides and influences analysts as they make probabilistic judgments about the unknown To provide routine to. Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) is a simple model for how to think about a complex problem when the available information is incomplete or ambiguous, as typically happens in intelligence.

Richards 'Dick' J. Heuer, Jr. was a CIA veteran of 45 years and most known for his work on analysis of competing hypotheses and his book, Psychology of Intelligence Analysis.[3] The former provides a methodology for overcoming intelligence biases while the latter outlines how mental models and natural biases impede clear thinking and analysis. Throughout his career, he worked in collection operations, counterintelligence, intelligence analysis and personnel security.[4] In 2010 he co-authored a book with Randolph (Randy) H. Pherson titled Structured Analytic Techniques for Intelligence Analysis.[5]

Background[edit]

Richards Heuer graduated in 1950 from Williams College with a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy. One year later, while a graduate student at the University of California in Berkeley, future CIA Director Richard Helms recruited Heuer to work at the Central Intelligence Agency.[3] Helms, also a graduate of Williams College, was looking for recent graduates to hire at CIA.[3] Heuer spent the next 24 years working with the Directorate of Operations before switching to the Directorate of Intelligence in 1975. His interest in intelligence analysis and 'how we know' was rekindled by the case of Yuri Nosenko and his studies in social science methodology while a master's student at the University of Southern California.[3] Richards Heuer is well known for his analysis of the extremely controversial and disruptive case of Soviet KGB defector Yuri Nosenko, who was first judged to be part of a 'master plot' for penetration of CIA but was later officially accepted as a legitimate defector. Heuer worked within the DI for four years, eventually retiring in 1979 after 28 years of service as the head of the methodology unit for the political analysis office. (Though retired from the DI in 1979, Heuer continued to work as a contractor on various projects until 1995.)[3] He eventually received an M.A. in international relations from the University of Southern California.[4] Heuer discovered his interest in cognitive psychology through reading the work of Kahneman and Tversky subsequent to an International Studies Association (ISA) convention in 1977. His continuing interest in the field and its application to intelligence analysis led to several published works including papers, CIA training lectures and conference panels.[6]

Structured analytic techniques[edit]

Structured Analytic Techniques for Intelligence Analysis and key concepts[edit]

Analysis Of Competing Hypotheses Software

Heuer's book Structured Analytic Techniques for Intelligence Analysis, published in 2010 (second edition 2015) and co-authored with Randy H. Pherson, provides a comprehensive taxonomy of structured analytic techniques (SATs) pertaining to eight categories: decomposition and visualization, idea generation, scenarios and indicators, hypothesis generation and testing, cause and effect, challenge analysis, conflict management and decision support.[5] The book details 50 SATs (55 in the second edition) in step-by-step processes that contextualize each technique for use within the intelligence community and business community. The book goes beyond simply categorizing the various techniques by accentuating that SATs are processes that foster effective collaboration among analysts.[6]

Structured analytic techniques as process[edit]

In light of the increasing need for interagency analyst collaboration,[7] Heuer and Pherson advocate SATs as 'enablers' of collective and interdisciplinary intelligence products.[6] The book is a response to problems that arise in small group collaborative situations such as groupthink, group polarization and premature consensus.[7] Heuer's previous insight into team dynamics advocates the use of analytic techniques such as Nominal Group Technique and Starbursting for idea generation and prediction markets for aggregating opinions in response to the identified problems.[7] The book proposes SATs as not only a means for guiding collection and analysis, but also a means for guiding group interaction.[6]

Recommendations to the Director of National Intelligence[edit]

Heuer and Pherson assert that the National Intelligence Council (NIC) needs to serve as the entity that sets the standards for the use of structured analytic techniques within the intelligence community.[6] The Director of National Intelligence (DNI) could accomplish this by creating a new position to oversee the use of SATs in all NIC projects. Further, Heuer and Pherson suggest that the DNI create a 'center for analytic tradecraft' responsible for testing all structured analytic techniques, developing new structured analytic techniques and managing feedback and lessons learned regarding all structured analytic techniques throughout the intelligence community.[6]

Psychology of Intelligence Analysis and key concepts[edit]

Heuer's seminal work Psychology of Intelligence Analysis details his three fundamental points. First, human minds are ill-equipped ('poorly wired') to cope effectively with both inherent and induced uncertainty.[8] Second, increased knowledge of our inherent biases tends to be of little assistance to the analyst. And lastly, tools and techniques that apply higher levels of critical thinking can substantially improve analysis on complex problems.[8]

Mental models and perceptions[edit]

Mental models, or mind sets, are essentially the screens or lenses that people perceive information through.[8] Even though every analyst sees the same piece of information, it is interpreted differently due to a variety of factors (past experience, education, and cultural values to name merely a few).[8] In essence, one's perceptions are morphed by a variety of factors that are completely out of the control of the analyst. Heuer sees mental models as potentially good and bad for the analyst. On the positive side, they tend to simplify information for the sake of comprehension but they also obscure genuine clarity of interpretation.[8]

Therefore, since all people observe the same information with inherent and different biases, Heuer believes an effective analysis system needs a few safeguards. It should: encourage products that clearly show their assumptions and chains of inferences; and it should emphasize procedures that expose alternative points of view.[8] What is required of analysts is 'a commitment to challenge, refine, and challenge again their own working mental models.'[8] This is a key component of his analysis of competing hypotheses; by delineating all available hypotheses and refuting the least likely ones, the most likely hypothesis becomes clearer.

Recommendations[edit]

Heuer offers several recommendations to the intelligence community for improving intelligence analysis and avoiding consistent pitfalls. First, an environment that not only promotes but rewards critical thinking is essential.[3] Failure to challenge the first possible hypothesis simply because it sounds logical is unacceptable. Secondly, Heuer suggests that agencies expand funding for research on the role that cognitive processes play in decision making.[3] With so much hanging on the failure of success of analytical judgments, he reasons, intelligence agencies need to stay abreast of new discoveries in this field. Thirdly, agencies should promote the continued development of new tools for assessing information.[3]

Analysis of competing hypotheses[edit]

'Analysis of competing hypotheses (ACH) is an analytic process that identifies a complete set of alternative hypotheses, systematically evaluates data that is consistent and inconsistent with each hypothesis, and rejects hypotheses that contain too much inconsistent data.'[9] ACH is an eight step process to enhance analysis:[10]

- Identify all possible hypotheses

- Make a list of significant evidence and arguments

- Prepare a matrix to analyze the 'diagnosticity' of evidence

- Drawn tentative conclusions

- Refine the matrix

- Compare your personal conclusions about the relative likelihood of each hypothesis with the inconsistency scores

- Report your conclusions

- Identify indicators

Heuer originally developed ACH to be included as the core element in an interagency deception analysis course during the Reagan administration in 1984 concentrated on Soviet deception regarding arms deals.[6] The Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) in conjunction with Heuer developed the PARC ACH 2.0.5 software for use within the intelligence community in 2005.[11]

Involvement in the Nosenko case[edit]

During the 1980s, Richards Heuer was deeply involved in analyzing the controversial Yuri Nosenko case. His paper, Nosenko: Five Paths to Judgment, was originally published in 1987 in the CIA's classified journal Studies in Intelligence, where it remained classified for eight years. In 1995, it was then published in Inside CIA's Private World, Declassified Articles from the Agency's Internal Journal, 1955–1992.[12] The article is an explanation of how and why the errors associated with the Nosenko case occurred, and has been used for teaching deception analysis to analysts.

Heuer outlines five strategies for identifying truth in deception analysis cases, employing the Nosenko case as a use case throughout in order to demonstrate how analysts on the case failed to conclude that Nosenko was legitimate.[12] The five strategies presented in the article are:

- Motive approach: Identifying whether or not there is a motive for deception.

- Anomalies and inconsistencies approach: Searching for inconsistencies from or deviations the norm.

- Litmus test approach: Comparing the information from an unknown or new source with the information from a reliable or credible source.

- Cost accounting approach: Analyzing the opportunity cost for the enemy and the cost of conducting deception.

- Predictive test approach: Developing a tentative hypothesis and then comprehensively testing it.

Heuer states that though he was at one point a believer in 'the master plot' (deep and pervasive penetration of the CIA by the Soviets) due to reasoning elaborated in the anomalies and inconsistencies approach and the motive approach, he came to discount this theory and to accept Yuri Nosenko as bona fide after exercising the predictive test approach and the cost accounting approach.[12] Heuer maintains that considering the master plot was not unwise as it was a theory that should have been discussed in light of the information available at the time.[12]

The conclusion of the five strategies approach is that, as demonstrated by the Nosenko case, 'all five approaches are useful for complete analysis' and that an analyst should not rely on one strategy alone.[12]

Contributions in personnel security[edit]

During his 20 years as a consultant for the Defense Personnel Security Research Center (PERSEREC), Richards Heuer developed two encyclopedic websites: the Adjudicative Desk Reference and Customizable Security Guide and the Automated Briefing System.[13] Both are free to use and available in the public domain for download.

Adjudicative desk reference[edit]

This large database supplements the Intelligence Community Adjudicative Guidelines which specify 13 categories of behavior that must be considered before granting a security clearance. Heuer's product provides far more detailed information about why these behaviors are a potential security concern and how to evaluate their severity. Though this background information is not official government policy, the reference has been approved by the Security Agency Executive Advisory Committee as a tool for assisting security investigators and managers.[13] Appeals panels and lawyers have used it to deal with security clearance decisions, and it has also been proven useful to employee assistance counselors.

Online guide to security responsibilities[edit]

This tool provides an all-in-one source for introducing new personnel to all the various intricacies of security. Additionally, it provides a wealth of information for security professionals seeking to prepare awareness articles or briefings. The software covers a variety of topics including (but not limited to): protecting classified information, foreign espionage threats and methods, and computer vulnerabilities.[13] It is an updated version of the Customizable Security Guide. In hard copy format, there are over 500 pages of material.[13]

Awards[edit]

- (1987) Agency Seal Medallion: 'For developing and teaching an innovative methodology for addressing complex and challenging problems facing the intelligence community.'[8]

- (1988) CIA Recognition: 'For outstanding contribution to the literature of intelligence.'[4]

- (1995) U.S. Congress Certificate of Special Congressional Recognition: 'For outstanding service to the community.'[4]

- (1996) CIA Recognition: 'For work on countering denial and deception.'[4]

- (2000) International Association of Law Enforcement Intelligence Analysts (IALEIA) 'Publication of the Year' Award for Psychology of Intelligence Analysis[4]

- (2008) International Association for Intelligence Education (IAFIE) Annual Award for Contribution to Intelligence Education[4]

References[edit]

- ^Gourley, Bob (2018-08-24). 'Former CIA Officer Richards J. Heuer'. CTOVision.com. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- ^'Richards Heuer Obituary - Pacific Grove, California'. Legacy.com. 2018-08-22. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- ^ abcdefghDavis, Jack (1999). 'Improving Intelligence Analysis at CIA: Dick Heuer's Contribution to Intelligence Analysis'. cia.gov. Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2018-08-10. This is the Introduction to Heuer's book Psychology of Intelligence Analysis.

- ^ abcdefg'Amazon.com's Richards J. Heuer Jr. Page'. Amazon.com. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ^ abHeuer Jr., Richards J.; Pherson, Randolph H. (2015) [2010]. Structured Analytic Techniques for Intelligence Analysis (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: CQ Press. ISBN9781452241517. OCLC871688859.

- ^ abcdefgHeuer Jr., Richards J. (2009). 'The Evolution of Structured Analytic Techniques'(PDF). e-education.psu.edu. Retrieved 2018-09-10. Presentation to the National Academy of Science, National Research Council Committee on Behavioral and Social Science Research to Improve Intelligence Analysis for National Security, Washington, DC, December 8, 2009.

- ^ abcHeuer Jr., Richards J. (2008). 'Small Group Processes for Intelligence Analysis'(PDF). pherson.org. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2016-10-20. Retrieved 2018-09-10. Prepared for the Sherman Kent School, Central Intelligence Agency, 28 July 2008.

- ^ abcdefghHeuer, Richards J. (2001) [1999]. Psychology of Intelligence Analysis (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN978-1929667000. OCLC53813306.

- ^'ACH: Analysis of Competing Hypotheses'. pherson.org. Pherson Associates, LLC. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ^'Analysis of Competing Hypotheses: An Eight Step Process'(PDF). pherson.org. Pherson Associates, LLC. Retrieved 2018-09-10. A single-page document.

- ^'ACH2.0 Download Page'. parc.com. Archived from the original on 2018-08-17. Retrieved 2018-09-10. See also: 'The Open Source Analysis of Competing Hypotheses Project'. competinghypotheses.org. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ^ abcdeHeuer Jr., Richards J. (1987). 'Nosenko: Five Paths to Judgment'. In Westerfield, H. Bradford (ed.). Inside CIA's Private World: Declassified Articles From the Agency's Internal Journal, 1955–1992. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 379–414. ISBN978-0300060263. JSTORj.ctt5vm5td. OCLC31867339.

- ^ abcd'PERSEREC'. dhra.mil. Archived from the original on 2017-03-15.

Further reading[edit]

Analysis Of Competing Hypotheses Template

- 'Works of Richards J. Heuer, Jr'. pherson.org. Pherson Associates, LLC. Retrieved 2018-09-10. Some papers by Heuer.

| Information mapping |

|---|

| Topics and fields |

| Node–link approaches |

| See also |

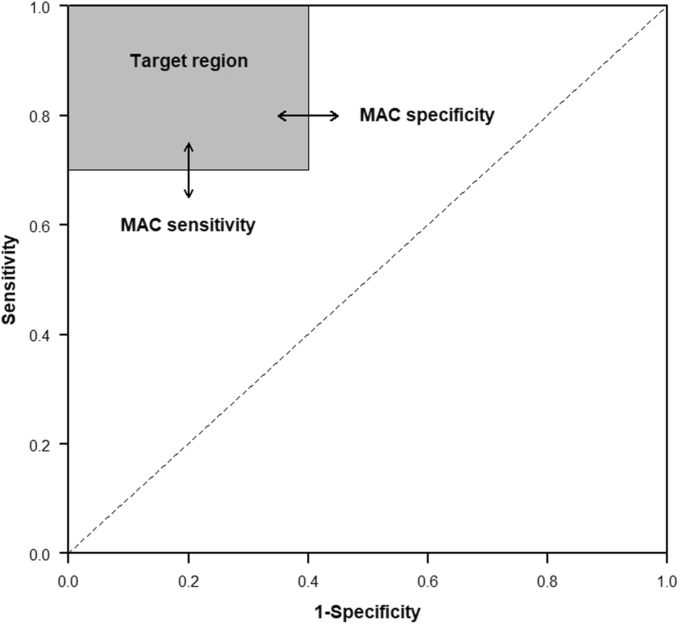

The analysis of competing hypotheses (ACH) is said to an unbiased methodology for evaluating multiple competing hypotheses for observed data. It was developed by Richards (Dick) J. Heuer, Jr., a 45-year veteran of the Central Intelligence Agency, in the 1970s for use by the Agency.[1] ACH is used by analysts in various fields who make judgments that entail a high risk of error in reasoning. It helps an analyst overcome, or at least minimize, some of the cognitive limitations that make prescient intelligence analysis so difficult to achieve.[1]

ACH was a step forward in intelligence analysis methodology, but it was first described in relatively informal terms. Producing the best available information from uncertain data remains the goal of researchers, tool-builders, and analysts in industry, academia and government. Their domains include data mining, cognitive psychology and visualization, probability and statistics, etc. Abductive reasoning is an earlier concept with similarities to ACH.

Process[edit]

Heuer outlines the ACH process in considerable depth in his book, Psychology of Intelligence Analysis.[1] It consists of the following steps:

- Hypothesis – The first step of the process is to identify all potential hypotheses, preferably using a group of analysts with different perspectives to brainstorm the possibilities. The process discourages the analyst from choosing one 'likely' hypothesis and using evidence to prove its accuracy. Cognitive bias is minimized when all possible hypotheses are considered.[1]

- Evidence – The analyst then lists evidence and arguments (including assumptions and logical deductions) for and against each hypothesis.[1]

- Diagnostics – Using a matrix, the analyst applies evidence against each hypothesis in an attempt to disprove as many theories as possible. Some evidence will have greater 'diagnosticity' than other evidence — that is, some will be more helpful in judging the relative likelihood of alternative hypotheses. This step is the most important, according to Heuer. Instead of looking at one hypothesis and all the evidence ('working down' the matrix), the analyst is encouraged to consider one piece of evidence at a time, and examine it against all possible hypotheses ('working across' the matrix).[1]

- Refinement – The analyst reviews the findings, identifies any gaps, and collects any additional evidence needed to refute as many of the remaining hypotheses as possible.[1]

- Inconsistency – The analyst then seeks to draw tentative conclusions about the relative likelihood of each hypothesis. Less consistency implies a lower likelihood. The least consistent hypotheses are eliminated. While the matrix generates a definitive mathematical total for each hypothesis, the analyst must use their judgment to make the final conclusion. The result of the ACH analysis itself must not overrule analysts' own judgments.

- Sensitivity – The analyst tests the conclusions using sensitivity analysis, which weighs how the conclusion would be affected if key evidence or arguments were wrong, misleading, or subject to different interpretations. The validity of key evidence and the consistency of important arguments are double-checked to assure the soundness of the conclusion's linchpins and drivers.[1]

- Conclusions and evaluation – Finally, the analyst provides the decisionmaker with his or her conclusions, as well as a summary of alternatives that were considered and why they were rejected. The analyst also identifies milestones in the process that can serve as indicators in future analyses.[1]

Strengths[edit]

There are many benefits of doing an ACH matrix. It is auditable. It is widely believed to help overcome cognitive biases, though there is a lack of strong empirical evidence to support this belief.[2] Since the ACH requires the analyst to construct a matrix, the evidence and hypotheses can be backtracked. This allows the decisionmaker or other analysts to see the sequence of rules and data that led to the conclusion.

Weaknesses[edit]

The process to create an ACH is time consuming. The ACH matrix can be problematic when analyzing a complex project. It can be cumbersome for an analyst to manage a large database with multiple pieces of evidence.

Especially in intelligence, both governmental and business, analysts must always be aware that the opponent(s) is intelligent and may be generating information intended to deceive.[3][4] Since deception often is the result of a cognitive trap, Elsaesser and Stech use state-based hierarchical plan recognition (see abductive reasoning) to generate causal explanations of observations. The resulting hypotheses are converted to a dynamic Bayesian network and value of information analysis is employed to isolate assumptions implicit in the evaluation of paths in, or conclusions of, particular hypotheses. As evidence in the form of observations of states or assumptions is observed, they can become the subject of separate validation. Should an assumption or necessary state be negated, hypotheses depending on it are rejected. This is a form of root cause analysis.

One of my favorite audio programsactually. These also require.And more free pluggos!!(careful with these, they used to crash my iMac)More Experimental Stuff:Check out this page for some far-out (and sometimes far-outdated)software for the adventuresome!- A graphical user interface (GUI) to the very powerful csound language.Even with no knowledge of csound, you can do amazing things. 1990s mac software system 07 pitchfork sin generator. If you know csound or want to learn it, have fun creatingthe most insane effects you can dream up - I think - and applying themto your sound files. My knowledgeof csound is very limited, but I still use this to apply insane effectsI have found nowhere else to my audio.

Evidence also presents a problem if it is unreliable. The evidence used in the matrix is static and therefore it can be a snapshot in time.

According to social constructivist critics, ACH also fails to stress sufficiently (or to address as a method) the problematic nature of the initial formation of the hypotheses used to create its grid. There is considerable evidence, for example, that in addition to any bureaucratic, psychological, or political biases that may affect hypothesis generation, there are also factors of culture and identity at work. These socially constructed factors may restrict or pre-screen which hypotheses end up being considered, and then reinforce confirmation bias in those selected.[5]

Philosopher and argumentation theoristTim van Gelder has made the following criticisms:[6]Password lock a folder mac app.

- ACH demands that the analyst makes too many discrete judgments, a great many of which contribute little if anything to discerning the best hypothesis

- ACH misconceives the nature of the relationship between items of evidence and hypotheses by supposing that items of evidence are, on their own, consistent or inconsistent with hypotheses.

- ACH treats the hypothesis set as 'flat', i.e. a mere list, and so is unable to relate evidence to hypotheses at the appropriate levels of abstraction

- ACH cannot represent subordinate argumentation, i.e. the argumentation bearing up on a piece of evidence.

- ACH activities at realistic scales leave analysts disoriented or confused.

Van Gelder proposed hypothesis mapping (similar to argument mapping) as an alternative to ACH.[7][8]

Structured analysis of competing hypotheses[edit]

The structured analysis of competing hypotheses offers analysts an improvement over the limitations of the original ACH.[discuss][9] The SACH maximizes the possible hypotheses by allowing the analyst to split one hypothesis into two complex ones.

For example, two tested hypotheses could be that Iraq has WMD or Iraq does not have WMD. If the evidence showed that it is more likely there are WMDs in Iraq then two new hypotheses could be formulated: WMD are in Baghdad or WMD are in Mosul. Or perhaps, the analyst may need to know what type of WMD Iraq has; the new hypotheses could be that Iraq has biological WMD, Iraq has chemical WMD and Iraq has nuclear WMD. By giving the ACH structure, the analyst is able to give a nuanced estimate.[10]

Other approaches to formalism[edit]

One method, by Valtorta and colleagues uses probabilistic methods, adds Bayesian analysis to ACH.[11] A generalization of this concept to a distributed community of analysts lead to the development of CACHE (the Collaborative ACH Environment),[12] which introduced the concept of a Bayes (or Bayesian) community. The work by Akram and Wang applies paradigms from graph theory.[13]

Other work focuses less on probabilistic methods and more on cognitive and visualization extensions to ACH, as discussed by Madsen and Hicks.[14] DECIDE, discussed under automation is visualization-oriented.[15]

Work by Pope and Jøsang uses subjective logic, a formal mathematical methodology that explicitly deals with uncertainty.[16] This methodology forms the basis of the Sheba technology that is used in Veriluma's intelligence assessment software.

Automation[edit]

A few online and downloadable tools help automate the ACH process. These programs leave a visual trail of evidence and allow the analyst to weigh evidence.

PARC ACH 2.0[17] was developed by Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) in collaboration with Richards J. Heuer, Jr. It is a standard ACH program that allows analysts to enter evidence and rate its credibility and relevance. Another useful program is the Decision Command software created by Dr. Willard Zangwill.[18]

SSS Research, Inc. is an analytic research firm that created DECIDE.[15][19] DECIDE not only allows analysts to manipulate ACH, but it provides multiple visualization products.[20]

There is at least one open-source ACH implementation.[21]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ abcdefghiHeuer, Richards J., Jr, 'Chapter 8: Analysis of Competing Hypotheses', Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency

- ^Thomason, Neil (2010), 'Alternative Competing Hypotheses', Field Evaluation in the Intelligence and Counterintelligence Context: Workshop Summary, National Academies Press

- ^Elsaesser, Christopher; Stech, Frank J. (2007), 'Detecting Deception', in Kott, Alexander; McEneaney, William (eds.), Adversarial Reasoning: Computational Approaches to Reading the Opponent’s Mind, Chapman & Hall/CRC, pp. 101–124

- ^Stech, Frank J.; Elsaesser, Christopher, Deception Detection by Analysis of Competing Hypotheses(PDF), MITRE Corporation, archived from the original(PDF) on 2008-08-07, retrieved 2008-05-01 MITRE Sponsored Research Project 51MSR111, Counter-Deception Decision Support

- ^Chapters one to four, Jones, Milo L. and; Silberzahn, Philippe (2013). Constructing Cassandra, Reframing Intelligence Failure at the CIA, 1947-2001. Stanford University Press. ISBN978-0804793360.

- ^van Gelder, Tim (December 2008), 'Can we do better than ACH?', AIPIO News, Australian Institute of Professional Intelligence Officers (Issue 55)

- ^van Gelder, Tim (11 December 2012). 'Exploring new directions for intelligence analysis'. timvangelder.com. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^Chevallier, Arnaud (2016). Strategic Thinking in Complex Problem Solving. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 113. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190463908.001.0001. ISBN9780190463908. OCLC940455195.

- ^Wheaton, Kristan J., et al. (November–December 2006), 'Structured Analysis of Competing Hypotheses: Improving a Tested Intelligence Methodology'(PDF), Competitive Intelligence Magazine, 9 (6): 12–15, archived from the original(PDF) on 2007-09-28, retrieved 2008-05-01

- ^Chido, Diane E., et al. (2006), Structured Analysis Of Competing Hypotheses: Theory and Application, Mercyhurst College Institute for Intelligence Studies Press, p. 54

- ^Valtorta, Marco; et al. (May 2005), 'Extending Heuer's Analysis of Competing Hypotheses Method to Support Complex Decision Analysis', International Conference on Intelligence Analysis Methods and Tools(PDF)

- ^Shrager, J., et al. (2009) Soccer science and the Bayes community: Exploring the cognitive implications of modern scientific communication. Topics in Cognitive Science, 2(1), 53–72.

- ^Akram, Shaikh Muhammad; Wang, Jiaxin (23 August 2006), 'Investigative Data Mining: Connecting the dots to disconnect them', Proceedings of the 2006 Intelligence Tools Workshop(PDF), pp. 28–34

- ^Madsen, Fredrik H.; Hicks, David L. (23 August 2006), 'Investigating the Cognitive Effects of Externalization Tools', Proceedings of the 2006 Intelligence Tools Workshop(PDF), pp. 4–11

- ^ abCluxton, Diane; Eick, Stephen G., ''DECIDE Hypothesis Visualization Tool'', 2005 Intl conf on Intelligence Analysis(PDF), archived from the original(PDF) on 2008-08-07, retrieved 2008-05-01

- ^Pope, Simon; Josang, Audun (June 2005), Analysis of Competing Hypotheses using Subjective Logic (ACH-SL), Queensland University, Brisbane, Australia, ADA463908

- ^Xerox Palo Alto Research Center and Richards J. Heuer, ACH2.0.3 Download Page: Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH), archived from the original on 2008-03-18, retrieved 2008-03-13

- ^Zangwill, Willard, Quantinus Biography

- ^Lankenau, Russell A., et al. (July 2006), SSS Research, Inc. – DECIDE, VAST 2006 Contest Submission

- ^SSS Research, DECIDE: from Complexity to Clarity, archived from the original on March 28, 2007

- ^'Competing Hypotheses'. competinghypotheses.org. Retrieved 2017-06-15.